One of the most pressing challenges facing Kenyan agriculture is the exodus of young people from farming. Youth—aged 18 to 35—represent the future workforce and innovation potential of the agricultural sector, yet they are increasingly turning away from farming as a livelihood. Instead, many pursue urban employment, informal sector work, or migration abroad. Those who remain in rural areas often view farming as a temporary fallback rather than a desirable career.

This youth exodus has profound implications. It depletes rural areas of productive labor and entrepreneurial energy. It fragments knowledge transfer, as fewer young people learn traditional farming practices from parents. It weakens institutions that depend on youth participation. And it leaves aging farmers without succession plans or family labor to maintain productivity.

The causes of youth disengagement from agriculture are typically described in surface terms: poor returns, hard labor, lack of finance, or the allure of city life. These observations contain truth but miss the underlying system dynamics. The real story is more complex and more tractable. Youth are not inherently opposed to agriculture; rather, they are responding rationally to a set of structural conditions that make agriculture seem unattractive compared to alternatives. Understanding these conditions and the feedback loops that perpetuate them is essential to addressing youth participation.

Jump to Section

Part One: Why Youth Are Leaving Agriculture

The Income Reality and Comparative Disadvantage

For a young person making a career choice, agriculture as currently practiced in rural Kenya is genuinely less attractive than alternatives—not because of irrational preferences, but because of real economic differences.

Small-scale farming in Kenya typically generates annual household incomes of 30,000 to 100,000 Kenya Shillings (KES), often irregular and seasonal. In contrast, even unskilled urban employment—working in retail, transportation, security, or the informal sector—can generate 200,000 to 400,000 KES annually, with more predictable monthly cash flow. Skilled urban employment generates substantially more.

For a young person with ambition and options, the economic case for staying in farming is weak. The difference in income is not marginal; it is a multiple of two to four times. Over a decade, that compounds into a substantial lifetime earnings difference.

Youth are not irrational in choosing higher income. They are responding to real economic incentives. The problem is not youth preference but the structure of agricultural returns.

Lack of Visibility Around Agricultural Income Potential

However, the income comparison is not simply between actual small-scale farming and actual urban employment. It is also shaped by what youth believe is possible in agriculture versus what they believe is possible in urban contexts.

Many young people have limited visibility into the actual income potential of agricultural entrepreneurship. They see their parents or relatives farming at low intensity, generating modest incomes, often struggling with debt or low yields. They extrapolate from this visible experience to assume that farming will always be like this—low-income, uncertain, and unrewarding.

What they often do not see are the agricultural entrepreneurs in their region or nearby regions who have successfully shifted to higher-value production, market-oriented farming, or agribusiness. They do not see the youth who have built substantial incomes through horticulture, dairy, poultry, or input distribution. These successes exist but are often invisible to rural youth because they are geographically dispersed, not systematically communicated, and embedded in social networks that youth have not yet accessed.

The contrast with urban opportunities is sharper because urban examples are more visible. A young person in a rural area can see, through social media, family members, or visitors, the material success of youth in cities. These examples are vivid and concrete, even if they also represent survivorship bias (successful urban youth are more visible than the many who struggle or fail).

Poor Working Conditions and Labor Quality

Beyond income, the day-to-day experience of farming is often unattractive to youth. Agricultural labor is physically demanding, often involving long hours in sun, heat, and rain. The work is repetitive and can feel monotonous compared to more varied occupations. There is little prestige or social status associated with being a small-scale farmer.

Young people, especially those with some formal education, increasingly see farming as drudgery—something their parents did out of necessity, not something they aspire to. The alternative—sitting in an office, working in a shop, or doing almost any non-manual work—feels like upward mobility, a sign of progress and development.

This preference for non-manual work is connected to how education and development are culturally framed. Formal education is presented as a pathway away from farming, toward better opportunities. Completion of secondary or tertiary education is meant to open doors to non-agricultural employment. For many young people and their families, this is the entire purpose of education—to escape farming.

Uncertainty and Risk Perception

Agricultural production is inherently uncertain. Rainfall is unpredictable. Pests and diseases threaten crops. Market prices fluctuate. For a young person trying to build a stable life—to establish a household, educate children, build assets—this uncertainty is unattractive.

In contrast, even modest urban employment often feels more certain. There is typically a wage, however small, that comes monthly. There is some degree of predictability even if it is imperfect.

Youth are particularly sensitive to risk because they have limited assets to buffer against failure. An older farmer with established land and household assets can weather a poor season. A young person with no capital, no experience, and no safety net cannot. The rational response to this asymmetry is to seek more certain income pathways.

Limited Access to Land and Capital

Historically, young farmers could inherit or access family land to establish themselves in agriculture. This pathway is increasingly blocked. Population pressure has fragmented landholdings. Younger children often have minimal viable plots. Land laws have created complexity around inheritance. And for youth who migrate to cities, return to access family land may feel like failure.

Capital is also difficult for youth to access. Banks require collateral that young people typically lack. Family credit is limited when family members are themselves under financial pressure. Youth are often excluded from credit programs designed for “established farmers.”

Without land and capital, the barriers to entry into agriculture are high. It is easier to borrow a few thousand shillings for transport services or retail than to assemble the land and capital needed for viable agricultural production.

Lack of Market Orientation and Value Addition Opportunities

Youth with entrepreneurial ambitions find limited expression for those ambitions within traditional small-scale farming. The pathway—buy inputs, plant, harvest, sell to trader—is not entrepreneurial; it is just replicating what everyone else does.

In contrast, urban informal business offers more apparent entrepreneurial opportunity. A young person can start a mobile phone repair business, a small retail shop, or a transportation service with relatively little capital and with room to innovate and grow. The business feels like theirs to build and improve.

Youth-led agricultural entrepreneurship—moving into high-value crops, processing, market-oriented production, or agribusiness—often requires capital, market knowledge, and business skills that are not easily accessible. It feels like it belongs to older, more established farmers, not to youth just starting out.

Part Two: The Structural Drivers of Youth Disengagement

Educational System Orientation Away From Agriculture

The educational system in Kenya, from primary through secondary level, is oriented toward urban employment. Agriculture, where it appears in curricula at all, is often framed as a low-status option or as practical training for students assumed to be unable to succeed in academic subjects.

Young people internalize this messaging. Success in education is understood as a pathway away from farming. A student who excels academically aspires to become a professional—teacher, doctor, engineer—not a farmer. This is not explicit messaging in most cases, but it is implicit in how education is structured, valued, and discussed.

Vocational training in agriculture exists but is often under-resourced and carries lower status than academic secondary education. Students who pursue agricultural vocational training may do so because they could not succeed in academic pathways, not because they are genuinely interested in agricultural careers. This further reduces the prestige of agricultural pathways.

The result is that the educational system systematically channels talented youth away from agriculture rather than developing agricultural professionals and entrepreneurs. The youth who might otherwise have vision and capacity to transform agriculture are directed into other sectors.

Weak Agricultural Extension and Youth Engagement

Government extension systems have limited capacity to engage youth. Extension officers are few, often based in towns, and typically focused on distributing inputs or promoting government programs rather than mentoring young farmers or discussing entrepreneurial opportunities.

There are few systematic mechanisms for youth to access business training, market information, or mentorship specific to agricultural entrepreneurship. Government programs occasionally target youth but often do so through generic business training rather than agriculture-specific pathways.

Private sector extension through input companies and traders focuses on input sales, not on building youth capacity or entrepreneurship.

The result is that youth interested in agriculture have limited access to the kind of professional guidance, mentorship, and opportunity exposure that would help them envision agricultural careers. They are left to learn from family and peers, who often operate within traditional, low-income farming models.

Limited Role Models and Visible Success Stories

Youth learn career aspirations partly through direct experience and partly through observation of role models. If you know successful agricultural entrepreneurs, agricultural professionals, or youth thriving in agriculture, farming becomes a more concrete and appealing possibility.

In many rural areas, visible role models in agriculture are limited. Successful agricultural entrepreneurs may exist regionally but are not well-known locally. Agricultural professionals (extension officers, input dealers, traders) may exist but are not presented as career exemplars. Youth in agricultural professions are not systematically highlighted or celebrated.

In contrast, role models in other sectors are more visible. Successful traders, transporters, hairdressers, and mobile phone dealers are locally visible. Relatives or friends working in cities are often highlighted and visited. Social media exposes youth to successful urban professionals and entrepreneurs.

The asymmetry in visible role models shapes aspirations. Youth aspire to what they can see as possible. When agricultural success is invisible, agricultural careers are not aspirational.

Family Pressure and Asset Inheritance Dynamics

Paradoxically, while young people are leaving agriculture, older farmers and parents often expect younger family members to continue farming or to return and maintain family farms. This creates tension.

Young people feel pressure to fulfill family expectations but simultaneously feel that agriculture offers limited opportunity. Some respond by leaving despite family expectations. Others stay resentfully, operating farms without genuine commitment or innovation. Still others maintain dual strategies—working in cities while maintaining nominal claims to family land or periodic returns.

Asset inheritance dynamics complicate this. In many cases, land is not formally distributed to younger children until parents die, or distribution is unclear. This means young people may lack secure access to land even when they want to farm. Or conversely, they may feel obligated to maintain family land without having security of tenure that would justify investment.

These dynamics often result in suboptimal outcomes: land is under-utilized, young people are stuck in unattractive situations, and family relationships are strained.

Gender Dimensions of Youth Agricultural Disengagement

Young women face particular barriers to agricultural participation. While agriculture employs substantial female labor, agricultural ownership, decision-making, and benefits are disproportionately male. Young women often see agriculture as low-paid labor for women—cultivation and harvesting—rather than as a career with progression and autonomy.

Land inheritance typically favors males. Young women often have insecure tenure even when they work in agriculture. Marriage typically involves moving to a husband’s farm or location, making investment in agricultural development uncertain.

Social norms around acceptable occupations for women mean that some young women are discouraged from pursuing certain agricultural ventures, preferring instead occupations with more apparent prestige or autonomy. The appeal of urban employment, even in difficult conditions, often exceeds the appeal of gendered agricultural labor.

Addressing youth agricultural participation requires deliberate attention to gender dynamics and creating pathways that are genuinely attractive and viable for young women, not just for young men.

Part Three: The Reinforcing Cycles

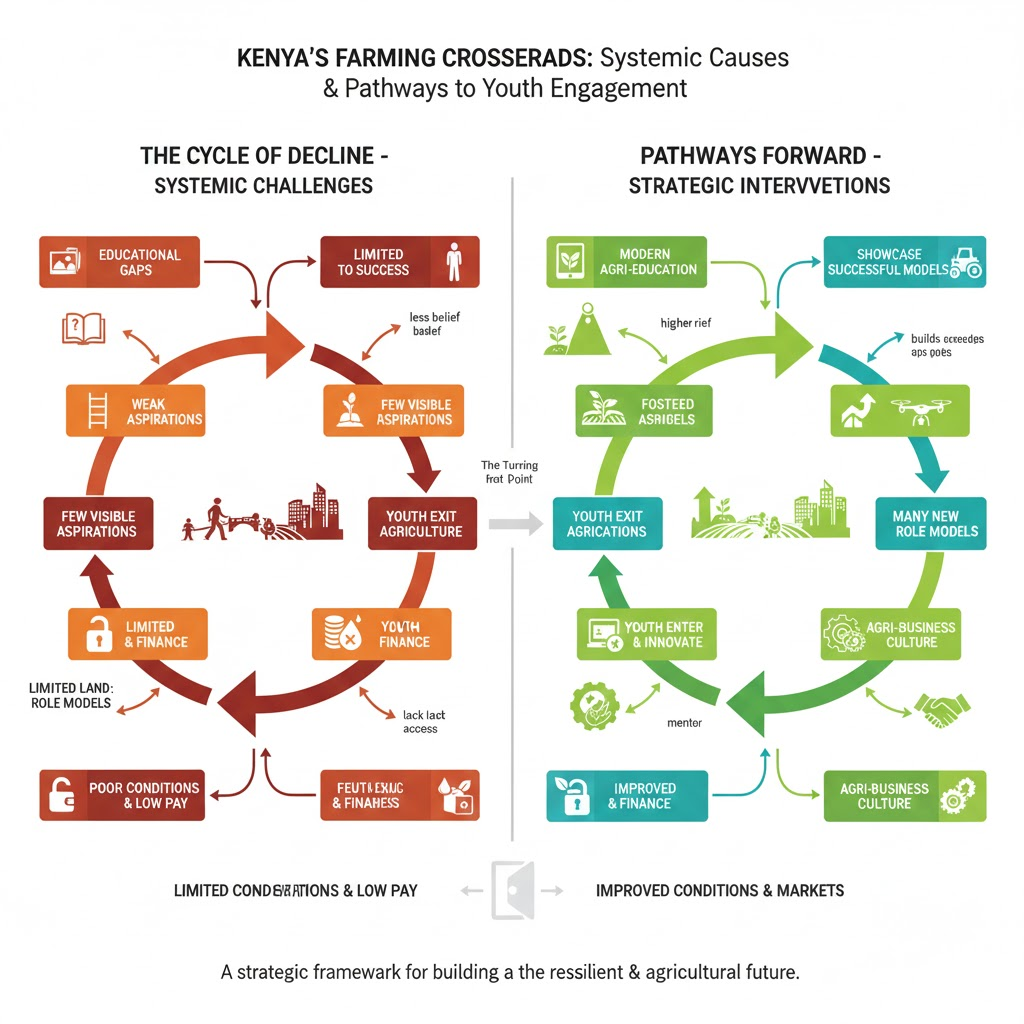

Youth agricultural disengagement is not simply the sum of individual choices responding to rational incentives. It is a system with reinforcing dynamics that amplify the initial pull factors and create a downward spiral.

The Aspiration-Visibility Cycle: As youth leave agriculture, fewer role models remain visible to younger cohorts. This reduces agricultural aspirations among the next generation. Lower aspirations drive further exits. The cycle repeats, progressively reducing the visibility of agriculture as a viable career option.

The Institutional Decay Cycle: Institutions serving agriculture—farmer organizations, cooperatives, extension systems, local government agricultural functions—depend partly on youth participation for vitality and renewal. As youth leave, these institutions weaken. Weakened institutions provide fewer services and opportunities for farmers, including youth who might stay. This further reduces the attractiveness of remaining, accelerating youth exit.

The Innovation Deficit Cycle: Youth bring energy for innovation and market engagement. As youth exit, the agricultural sector becomes more conservative and less responsive to market change. Innovation stalls. Competitiveness declines. Returns decline. Agriculture becomes even less attractive to youth. More youth leave.

The Knowledge Transfer Cycle: Young people learn farming from parents and elders. As fewer young people participate in farming, this intergenerational knowledge transfer breaks down. Farming becomes less connected to younger generations. When some youth do want to farm, they lack embedded knowledge and must learn from external sources rather than through family practice. This increases the learning curve and perceived difficulty.

The Demographic Aging Cycle: As youth leave, the agricultural population ages. An aging farm population is less productive, less innovative, and faces higher labor constraints. Agricultural productivity and viability decline. This makes agriculture even less attractive to youth. The population continues aging.

These cycles create a self-reinforcing downward spiral. Initial conditions—lower income in farming, appeal of urban alternatives—are amplified by system dynamics into accelerating youth disengagement. Simply addressing initial conditions (raising farm incomes, improving extension) may not be sufficient to overcome the momentum of these reinforcing cycles.

Part Four: Strategic Interventions to Reverse Youth Disengagement

Reframing Agriculture as an Entrepreneurial Opportunity

A fundamental shift is needed in how agriculture is presented to youth. Rather than presenting agriculture as traditional farming—replicating parent practices on inherited land—agriculture should be presented as a dynamic, entrepreneurial sector with diverse opportunities.

This requires deliberate communication showing the income potential of various agricultural ventures. Youth need to see, through case studies and media, examples of youth who have built substantial incomes through horticulture, dairy, poultry, agribusiness, input distribution, and value addition. These examples need to be specific, credible, and proximate—ideally from regions youth are familiar with or similar regions.

Extension programs, farmer organizations, and government should deliberately highlight youth agricultural entrepreneurs, celebrating their success and making them visible as role models. Social media, radio, and community platforms should feature these stories.

Agricultural ventures should be presented not as fallback options but as genuine business opportunities, with potential for income, growth, and autonomy comparable to other sectors.

Youth-Focused Agricultural Entrepreneurship Training

Youth need training specifically designed for agricultural entrepreneurship, not just generic business training or agronomic training. This training should address:

- Market-oriented thinking: How to identify market opportunities, understand customer needs, and position products for market success

- Value chain analysis: Understanding where value is created in agricultural value chains and where entrepreneurial opportunities exist

- Business planning: Creating simple business plans, financial projections, and go/no-go decision frameworks

- Risk management: Understanding and managing agricultural risks through diversification, insurance, and strategic planning

- Digital tools: Using mobile technology, social media, and online platforms for market access and information

Critically, this training should be delivered by successful agricultural entrepreneurs, not just by generic trainers. Youth respond better to peers and slightly-older role models than to external experts.

Training should be location-based, responding to local agricultural opportunities and markets rather than generic approaches. And it should be connected to finance—training is most effective when combined with pathways to access capital.

Youth Access to Finance for Agricultural Enterprises

Current finance mechanisms often exclude youth because they lack collateral, established credit history, or what lenders consider viable business proposals. Youth-specific finance mechanisms are needed.

These might include: youth-specific credit lines with lower collateral requirements; group lending where youth collectively secure loans; equity investment in youth-led ventures; or venture capital approaches for high-potential agricultural startups.

Finance should be available at amounts that make sense for youth ventures—often smaller than traditional agricultural loans but larger than microcredit. And finance should be coupled with business development support, so youth are not just given money but are supported in making good decisions about how to use it.

Importantly, some failed ventures should be expected and acceptable. Learning to manage failure is part of entrepreneurial development. Finance mechanisms that penalize failure too heavily will discourage risk-taking and learning.

Youth-Focused Land Access and Tenure Security

Without viable pathways to access land, youth cannot establish agricultural enterprises. Several approaches can help:

- Clearer inheritance rules: Family and local government support for clearer, more transparent processes for distributing inherited land to younger generations

- Rental and leasing: Formalizing processes for youth to rent or lease land from older farmers, with transparent terms and security of tenure

- Communal or group land access: Where communal land exists, formalizing youth access through group arrangements

- Urban-to-rural investment: Supporting youth and diaspora to purchase agricultural land for commercial purposes

Land access solutions need to address gender explicitly, ensuring young women have secure pathways to access and control land.

Integration of Agriculture into Education Systems

Education systems should integrate agriculture not as a low-status vocational option but as a professional and entrepreneurial pathway. This might include:

- Business-oriented agricultural training: Secondary and tertiary education that presents agriculture as a business sector with entrepreneurial opportunities

- Agricultural science and technology: Training in modern agricultural methods, technology, and innovation

- Connecting students with practitioners: Internships, mentorships, and exposure to agricultural professionals and entrepreneurs

- Demonstration and experimentation: School farms or partnerships with working farms where students learn through practice

Importantly, agricultural education should not be separate from or lower-status than academic pathways. It should be presented as a legitimate professional track for ambitious students.

Institutional Support for Youth-Led Farmer Organizations

Youth often lack leadership roles in existing farmer organizations and cooperatives. Creating youth-specific groups or ensuring youth representation in mixed groups can build institution ownership and engagement among youth.

Youth organizations should focus on entrepreneurship and market engagement, not just production. They should be vehicles for peer learning, collective business ventures, and advocacy for youth agricultural interests.

Supporting capable youth to take leadership roles in these organizations builds their skills and confidence while revitalizing organizations with energy and new perspectives.

Creating Youth Agricultural Hubs and Demonstration Spaces

Physical or virtual spaces where youth can learn about agricultural opportunities, access mentoring, and connect with peers and customers can be powerful catalysts. Youth agricultural hubs might include demonstration farms, training spaces, market linkage centers, or digital platforms.

These hubs should be managed by or heavily involve youth, creating spaces that feel relevant and ownership-oriented rather than top-down institutions.

Hubs can serve multiple functions: showcasing successful agricultural enterprises, providing training, facilitating peer learning, connecting youth with finance and markets, and creating spaces where agricultural entrepreneurship is visible and normalized.

Gender-Intentional Programming

Women-specific agricultural entrepreneurship programs can address the particular barriers young women face. These might include training in market-oriented agriculture, support for land access, mentoring from successful female entrepreneurs, and spaces for collective organization around agricultural interests.

Additionally, mixed programming should deliberately attend to gender dynamics, ensuring that training and opportunities genuinely benefit both men and women and do not reinforce existing gender inequalities.

Part Five: System-Level Requirements

Cross-Sector Coordination

Addressing youth participation requires coordinated action across education, finance, extension, land administration, and market systems. No single intervention will be sufficient. Government, private sector, NGOs, and farmer organizations all have roles to play.

Coordination mechanisms—formal or informal—that bring these actors together to align on youth agricultural development can dramatically increase impact and reduce duplication or misalignment.

Long-Term Investment and Patience

Building youth participation is a multi-year undertaking. Changes in education systems, institutional development, and cultural narratives about agriculture develop over time. Early interventions may show limited immediate impact, but create conditions for scaling impact over years.

Short-term projects with fixed timelines often fail to achieve durable change in youth participation. Sustained commitment is needed.

Measuring Progress on Aspirations and Perception

While agricultural income and production are important metrics, progress on youth participation should also be measured through shifts in how youth perceive agriculture. Do youth see agricultural entrepreneurship as feasible? Do they aspire to agricultural careers? Are young people with education seeking agricultural opportunities?

These aspirational and perceptual shifts often precede behavioral change. Monitoring them allows for course correction and provides evidence of progress even before agricultural outcomes shift.

Conclusion

Youth are leaving agriculture in Kenya not because they are irrational or lack capability, but because the structure of agricultural opportunity, the visibility of alternatives, and the institutional environment make other sectors more attractive. These structural factors can be changed.

By reframing agriculture as an entrepreneurial opportunity, providing youth-focused training and finance, ensuring viable pathways to land access, integrating agriculture into education systems, and building institutional support for youth participation, Kenya can reverse the trend of youth agricultural disengagement.

This transformation will not happen quickly or easily. But it is possible. The energy, innovation, and market orientation that youth bring could revitalize Kenyan agriculture. Creating structures and incentives that attract youth participation is therefore one of the most important investments for agricultural transformation.