- 3816 Cherry Ave NE Salem, Oregon

- Plumbingservice@mail.com

- 3816 Cherry Ave NE

In development discourse surrounding Kenyan agriculture, the narrative is almost always about access—access to finance, access to markets, access to better inputs. Yet behind every policy recommendation lies an implicit assumption: that farmers know what they would do if they had money, or that they understand the opportunities available to them. This assumption is often wrong.

The real bottleneck constraining agricultural entrepreneurship in Kenya is not primarily financial or infrastructural. It is cognitive and aspirational. Many Kenyan small-scale farmers lack the vision, mental models, and frameworks necessary to imagine their farms as businesses with multiple pathways to growth and value creation. They cannot articulate ideas worth financing because they have never encountered the possibility that such ideas exist or that such transformation is achievable for someone like them.

This is the root cause that development interventions have largely overlooked: the absence of entrepreneurial thinking itself. Until this foundational gap is addressed, expanding access to credit or markets will have limited impact. A farmer without an idea cannot use a loan productively. A farmer without market awareness cannot recognize opportunities. A farmer without exposure to alternative models cannot envision a different future.

This essay explores why this vision gap exists, how it perpetuates itself, and what interventions might genuinely unlock entrepreneurial thinking among Kenyan farmers—not as a quick fix, but as a systemic shift in how farming is understood and practiced.

Farming in rural Kenya has historically been framed as a livelihood—a way of life and source of subsistence passed down through generations. Parents teach children how to plant, when to harvest, which crops grow in their soil, and how to manage through dry seasons. This knowledge is valuable and hard-won, accumulated through generations of experience with local conditions.

However, this livelihood framing creates a specific mental model: farming is something you do the way it has always been done. The goal is to feed your family, generate some cash for immediate needs, and maintain the cycle. Success is measured in terms of survival and stability, not growth or transformation.

In contrast, a business mindset frames farming as a value creation activity with multiple possible pathways and scaling potential. A farmer with a business mindset asks different questions: What do customers want? What are they willing to pay? How can I reduce costs or improve quality? What could I do with my land and labor beyond traditional production? Where are the inefficiencies in the value chain I could exploit?

These are not necessarily questions that arise naturally from a subsistence farming background. They require exposure to market thinking, examples of innovation, and a belief that such transformation is possible for people in your situation.

Most small-scale Kenyan farmers operate primarily within the livelihood mindset. This is not a personal failing; it is rational adaptation to their circumstances and what they have been exposed to. When you are uncertain about your next harvest and your children’s school fees are due, planning a sophisticated value-addition business feels like a luxury you cannot afford—or worse, a risk you cannot take.

Knowledge about farming is primarily transferred through families and communities. Children learn by doing alongside parents. Practices and assumptions about what is possible get embedded early and reinforced through daily experience and observation of peers.

Critically, this intergenerational transfer does not automatically include exposure to innovation or alternative models. A child who has never seen anyone in their village process crops into value-added products will not grow up imagining themselves doing so. A teenager who knows that everyone in their community sells their harvest to the same middleman will not naturally question whether other markets exist.

The problem is compounded by the fact that successful innovations are often localized. A farmer in one part of Kenya who has successfully moved into horticulture production or dairy processing may be entirely invisible to farmers in another region—not because information technology is lacking (though that is sometimes true), but because social networks, value chains, and information channels are fragmented. Farmers primarily learn from their immediate social sphere.

This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: farms in a given area operate in broadly similar ways because that is how everyone operates, because that is what farmers learned from family and peers, because no one around them has done anything different. Breaking this cycle requires injecting new examples and possibilities into the social learning process.

Even if a farmer were to imagine an entrepreneurial opportunity, economic pressures often make pursuing it extremely difficult. Small-scale farmers in Kenya operate on thin margins. Most farm plots are less than one hectare. Yields are often low due to poor soil, limited access to quality inputs, or suboptimal practices. Income is seasonal and uncertain.

In this context, time poverty is as real as financial poverty. When you are working dawn to dusk to maintain current production levels and generate subsistence income, finding time to explore new opportunities, attend training, or plan a business transition is luxurious. When your cash flow is unpredictable and your savings are minimal, taking on even a small risk—trying a new crop variety, investing in equipment for value addition—feels potentially catastrophic.

Temporal poverty also constrains cognitive capacity. Neuroscientific and behavioral economics research has shown that people operating under scarcity—whether financial or temporal—have reduced cognitive bandwidth for long-term planning and complex decision-making. A farmer preoccupied with immediate survival is less able to engage in the kind of creative, future-oriented thinking that entrepreneurship requires.

This is not a moral failing or lack of capability. It is a predictable human response to constraint. The implication is that creating space for entrepreneurial thinking—through reduced time pressures, basic income security, or deliberate protected spaces for learning and planning—is a prerequisite, not an afterthought.

Most Kenyan small-scale farmers have limited visibility into value chains beyond their immediate role. A maize farmer knows the price they receive from traders at the farm gate. They do not necessarily know what that maize sells for at retail, what percentage goes to processors, what margins different value chain actors capture, or what price points would justify different production or processing approaches.

Similarly, farmers often lack information about market demand beyond what their immediate buyers tell them. A trader might say “I can only buy so much maize at this price,” and the farmer interprets that as a market constraint, without realizing that different buyers, different geographic markets, or different product forms (processed, packaged, certified) might offer different price points.

This information asymmetry is partially about access to data, but it is also about frameworks for understanding value chains. Many farmers have never been taught to think about value chains at all—to see the series of steps from production to consumer, the value added at each step, and the opportunities that exist in different links of the chain. Without this framework, information about markets feels random and disconnected rather than revealing a strategic landscape they could navigate.

Market linkage programs have shown that connecting farmers directly with buyers can be transformative—but the impact comes partly from the information transfer, the revelation of what is actually possible, not just from the logistical connection itself.

Entrepreneurship is substantially learned through observation and social influence. People are more likely to start businesses, try new approaches, or take entrepreneurial risks when they know others who have done so successfully. This is not just about inspiration; it is about making the path seem real and achievable.

In rural Kenya, successful agricultural entrepreneurs do exist—farmers who have moved into horticulture, dairy processing, greenhouse production, seed multiplication, agro-input distribution, or export-oriented production. However, these successes are often geographically dispersed and not systematically shared. A farmer in one county may never learn about a successful model being practiced 50 kilometers away in another county.

Additionally, successful farmer entrepreneurs often do not see themselves as teachers or mentors. Their success is individual; sharing their knowledge might feel like revealing competitive advantage. Extension services that could aggregate and disseminate this knowledge are often under-resourced and fragmented in coverage.

The consequence is that many farmers grow up and work their entire lives without ever encountering a lived example of an alternative way of farming—a neighbor, relative, or respected community member who has successfully pursued an entrepreneurial path and thrived.

Formal education in rural Kenya emphasizes academic subjects but rarely includes business fundamentals, market analysis, value chain thinking, or entrepreneurial mindset development. Vocational training programs exist but are unevenly distributed and often focused on specific skills rather than holistic business thinking.

Most Kenyan small-scale farmers left school at primary or secondary level. Their agricultural knowledge comes from family and community practice, not from systematic education. They may not have learned how to analyze a market, create a simple business plan, calculate unit costs, understand profit margins, or think about competitive advantage.

This is not a failing of individual farmers but a gap in what educational institutions and extension services have traditionally offered to rural agricultural communities. Without this foundational business education, even a farmer who is exposed to an opportunity may not have the framework to evaluate it or plan how to pursue it.

Farming in much of rural Kenya carries cultural meanings beyond economics. It is tied to land ownership, family stability, and identity. For many communities, farming is what you do—not because you analyzed market opportunities and decided it was the best use of capital, but because your family has always farmed this land.

Related to this is a narrative distinction between “farming” (what people do) and “business” (something others do in towns). This distinction is not always explicit but appears in how people talk about their aspirations. A young person might want to “go to the city and do business” as an alternative to staying and farming, rather than imagining farming itself as a business.

This narrative matters because it shapes what young people aspire to and what kinds of transformation they imagine possible. If farming is categorically different from business, then a young person with entrepreneurial ambitions might see no pathway to realize those ambitions within agriculture.

Interestingly, this narrative is not immutable. In areas where agricultural entrepreneurship has become more visible and normalized—where successful farmer entrepreneurs are known and respected—the distinction between farming and business blurs. Young people begin to see agribusiness as a legitimate and desirable pathway.

Kenya’s agricultural extension system has contracted significantly over recent decades. The ratio of extension officers to farmers is very high in many areas, meaning that individual farmers rarely have sustained access to professional agricultural advice. Extension officers, where they exist, are often focused on promoting specific government programs rather than providing responsive advice tailored to individual farmer circumstances and aspirations.

This means that information about innovations, market opportunities, and new approaches typically does not reach farmers through systematic professional channels. Instead, farmers rely on peers, traders, and input dealers—who may have incentives that do not align with the farmer’s best interest or who may not have comprehensive information themselves.

Farmer groups and cooperatives can partially fill this gap, but these are highly variable in quality and function. In some cases, they are active spaces for collective learning and business development. In others, they are dormant or function primarily for input buying.

The fragmentation of knowledge systems means that even when innovations exist and could benefit farmers, the pathways for farmers to learn about them are weak.

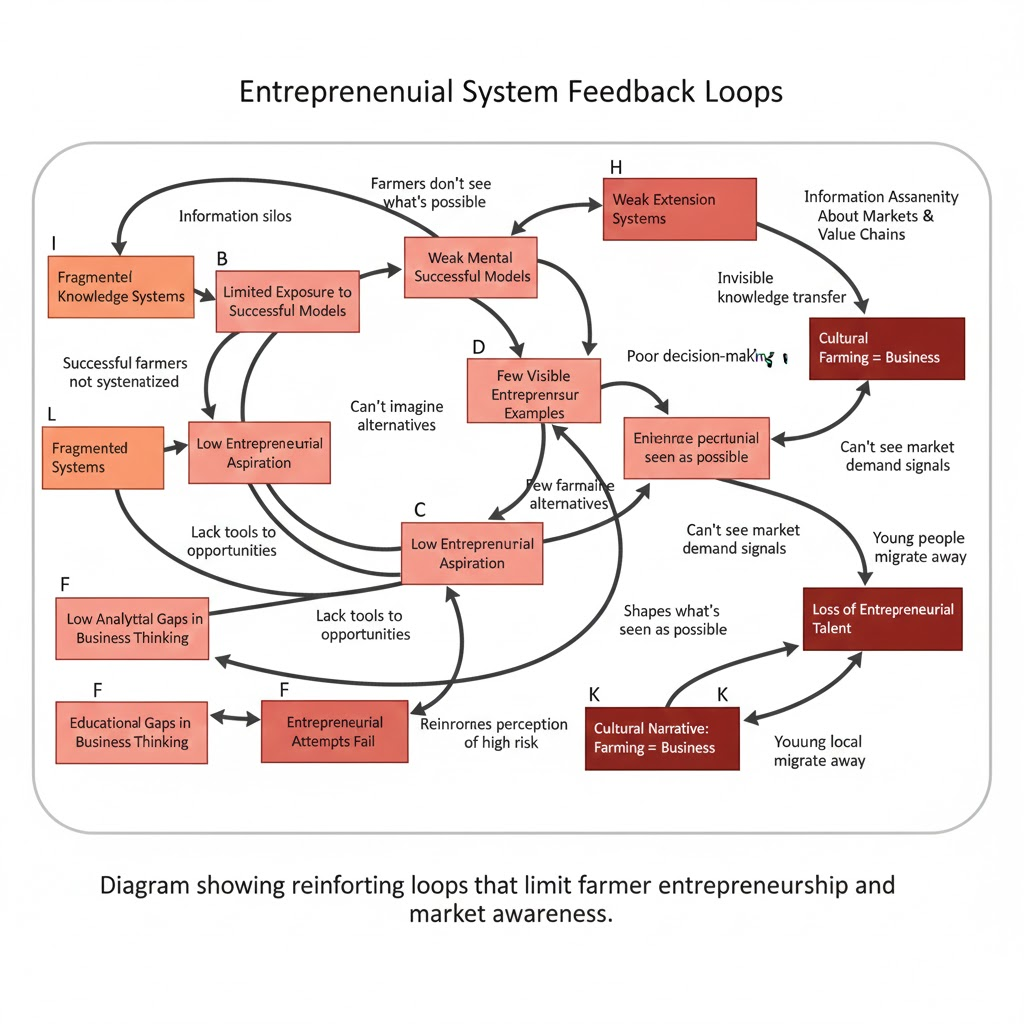

The vision gap is not just an initial condition; it is actively maintained by structural factors. Because farmers lack exposure to entrepreneurial models, they do not demand or seek out training in business thinking. Because they do not articulate business ideas, lenders do not expect to see business plans or market analysis from farmers. Because farmers are not engaging with formal business development services, those services remain underdeveloped in rural areas. Because entrepreneurial activity is rare, young people with ambitions see little opportunity in agriculture and migrate to cities.

Each of these dynamics reinforces the others. A farmer considering a new venture without exposure to successful models, without business training, without access to business development services, and without peer examples is undertaking something that feels risky and difficult. Most rationally decide not to attempt it.

This is not a failure of will or capability but a rational response to actual risk and isolation. Breaking this cycle requires intervention at multiple points simultaneously, not just removing one constraint (like providing credit) in isolation.

A farmer considering an entrepreneurial venture is engaging in risk calculation, probably implicitly rather than explicitly. They evaluate the chance of success, the magnitude of potential loss, their own capability, and the availability of support.

Without exposure to successful examples, risk perception is distorted. A venture that has been successfully executed by dozens of farmers elsewhere may seem impossibly risky to a farmer who has never seen anyone attempt it. Conversely, a venture that sounds like a minor variation on existing practice may seem safer than it actually is.

When farmers do see successful examples—through exposure to model farms, study visits, or community leaders who have succeeded—risk perception often shifts dramatically. The same venture that seemed high-risk becomes suddenly plausible.

Many development programs focus on removing supply-side constraints: providing credit, improving market access, distributing inputs. These interventions operate on the assumption that farmers know what they want to do and just need resources or connectivity to do it.

However, when the underlying constraint is that farmers do not have ideas about what to do, these programs have limited impact. A farmer who receives a loan but does not have a clear sense of what business opportunity to pursue may use it for consumption or make decisions reactively rather than strategically.

The most successful programs often include components that were not initially planned: exposure to successful models, business planning support, market exploration, or peer learning. These components address the vision gap, making the subsequent access to credit or markets actually transformative rather than merely injected money into an existing system.

Farmer Field Schools (FFS) are a proven model for agricultural learning, but they have typically focused on agronomic innovation (new crop varieties, improved practices) rather than business and entrepreneurship. Expanding FFS to include business and market analysis, value chain thinking, and exposure to alternative farming models could be transformative.

The model works because it operates within existing social structures, builds on peer learning and local leadership, and creates a protected space for experimentation and discussion. Incorporating entrepreneurial vision-building into this existing structure is relatively low-cost and highly contextual.

Additionally, FFS can be designed to include study visits—exposure to successful farmer entrepreneurs in other villages or counties. These visits are powerful not because they provide new information in the abstract but because they make possibilities visceral and real. Seeing a neighbor or similar farmer who has successfully shifted into value addition or market-oriented production changes risk perception and aspiration.

Deliberately identifying successful farmer entrepreneurs and creating structures for them to mentor and model for others is a high-leverage intervention. This works partly through explicit knowledge transfer but primarily through demonstrating that transformation is possible.

Farmer entrepreneurs are often embedded in their communities; they have credibility that external experts do not. They understand local conditions and constraints because they operate within them. Their example is therefore more compelling and more instructive than that of a development worker or trainer.

Programs that compensate farmer entrepreneurs for mentoring time, create formal mentorship relationships, or establish demonstration farms run by successful farmers have shown significant results in shifting entrepreneurial activity.

Farmers often operate with limited understanding of who their actual customers are, what those customers value, and what price points are realistic. Creating direct relationships between farmers and end-market actors—whether retailers, processors, exporters, or institutional buyers—can rapidly shift farmer understanding of what is possible.

Market exposure programs might include: facilitated visits to markets where farmers see how their products are sold and at what price; meetings with buyers who explain their purchasing criteria and volumes; or participation in producer networks that aggregate farmer supply to meet larger orders.

The value of these interactions is not just in establishing new sales channels, though that matters. It is in shifting farmer perception of market opportunity. Once a farmer understands that a buyer will pay premium prices for specific quality attributes, or that processing increases value by 300 percent, or that there is unmet demand for a particular product, their entrepreneurial thinking shifts. An opportunity that seemed invisible becomes obvious.

Formal business training is valuable, but generic business education often does not resonate with farmers or connect to their context. Training needs to be specifically designed for agricultural entrepreneurship and delivered in ways that connect to farmer experience and circumstances.

This might include: basic training on understanding costs and calculating margins; tools for simple business planning; strategies for market research and customer discovery within an agricultural context; understanding value chains; or negotiation skills for engaging with buyers.

Critically, this training should be delivered by people who understand agriculture, ideally by farmer entrepreneurs themselves or by agricultural extension professionals who have business training. The training should use agricultural examples and address the specific decision-making situations farmers face.

In urban areas, entrepreneurs routinely access business development services—accountants, business advisors, marketing consultants. These services are almost completely absent in rural agricultural areas.

Creating systems for farmers to access basic business development services—through mobile advisors, digital platforms, or community-based service providers—can dramatically improve entrepreneurial decision-making. A farmer considering a new venture benefits enormously from someone to help them think through the market opportunity, develop a simple business plan, and identify risks and solutions.

This does not require expensive urban-level consulting. Community-based service providers, trained youth, or digital platforms can provide cost-effective advisory services tailored to farmer needs.

Young people in rural Kenya often see agriculture as a fallback option rather than a desirable career. Yet youth bring energy, creativity, and openness to innovation that can be a tremendous asset in shifting agricultural entrepreneurship.

Programs that deliberately engage youth, reframe agriculture as an entrepreneurial opportunity, and create pathways for youth to lead agricultural innovation can shift sector dynamics. This requires not just training young farmers but also creating visible examples of young agricultural entrepreneurs, connecting youth with markets and opportunities, and supporting them to take early risks.

When young people see successful young agricultural entrepreneurs, when they understand the income potential of various agricultural ventures, and when they have access to finance and support, many choose to stay in or return to agriculture—with an entrepreneurial orientation rather than a subsistence one.

Farmer cooperatives have potential to be powerful vehicles for building entrepreneurial vision and capacity. Cooperatives can collectively access financing, engage with larger-scale markets, pool resources for value addition, and create forums for collective learning.

However, many existing cooperatives are weak or dysfunctional. Strengthening cooperatives requires attention to governance, leadership capacity, and the specific business strategies cooperatives will pursue. Cooperatives work best when they are member-driven—when farmers have a voice in decisions and see concrete benefits.

Well-functioning cooperatives can rapidly shift member perception of what is possible, particularly around collective ventures that individual farmers could not undertake alone (processing facilities, wholesale market access, input groups).

Digital technology creates new possibilities for exposing farmers to successful models, connecting with markets, and accessing business information. Platforms that aggregate information about prices, buyer requirements, and successful farmer practices can help level information asymmetries.

Mobile platforms, WhatsApp groups, and increasingly social media are becoming channels through which farmers learn from each other and from agricultural advisors. These platforms are most effective when they are actively managed to share practical information relevant to farmer decision-making.

Shifting entrepreneurial vision among Kenyan farmers requires coordinated change across multiple systems: education, extension, finance, markets, and social learning systems. Interventions in any one area have limited impact without supporting changes in others.

For example, business training is more effective when combined with exposure to successful models and access to finance. Market linkages are more effective when combined with business skills. Extension systems need to shift from purely agronomic advice to business-oriented support.

This requires coordination between government agencies, NGOs, private sector actors, and farmer organizations—coordination that does not currently occur systematically in most areas.

Building entrepreneurial vision is not a quick-fix intervention. It requires sustained engagement over years, not months. Young people who have never seen agricultural entrepreneurship as an option will not shift aspiration after a single training. Farmers embedded in subsistence-oriented systems will not immediately shift to business thinking after one market visit.

However, the good news is that change accelerates once it begins. As successful examples accumulate, as young people increasingly pursue agricultural entrepreneurship, as market systems develop around these new ventures, entrepreneurial behavior becomes normalized. What seemed impossible becomes standard.

Real transformation happens through local institutions and leadership—farmer organizations, community leaders, local service providers, and local government. External programs can catalyze change, but sustainability requires building local capacity and institutions to carry change forward.

This means investing in training farmer leaders, strengthening farmer organizations, supporting local youth and women to become service providers, and building farmer-led institutions that can support ongoing entrepreneurial activity. It is slower and less visible than running external training programs, but it is the pathway to durable change.

The vision gap constraining agricultural entrepreneurship in Kenya is real and significant. Many small-scale farmers lack the mental models, exposure to successful examples, business training, and confidence necessary to imagine and pursue entrepreneurial ventures in agriculture. This is not a personal failing but a rational response to limited exposure, economic pressures, and structural absence of supporting institutions.

Addressing this root cause requires deliberate, multi-faceted intervention: exposing farmers to successful entrepreneurial models, building business skills and market understanding, creating spaces for peer learning, reframing agriculture as an entrepreneurial opportunity, and building local institutions to support ongoing entrepreneurial activity.

These interventions are more complex than simply providing credit or markets. But they address the actual constraint: not money or information alone, but the capacity, confidence, and vision to imagine and pursue agricultural entrepreneurship. When this foundational capacity is built, everything else—finance, markets, inputs—becomes far more transformative.

The opportunity is significant. Rural Kenya contains millions of farmers and hundreds of millions of hectares of agricultural land. Even modest shifts in entrepreneurial orientation and capacity could generate substantial economic transformation and improved livelihoods. But that transformation requires first building the vision and thinking frameworks within which entrepreneurial action becomes possible.

09:00 Am - 11:00 Pm

© 2024 Created with Royal Elementor Addons